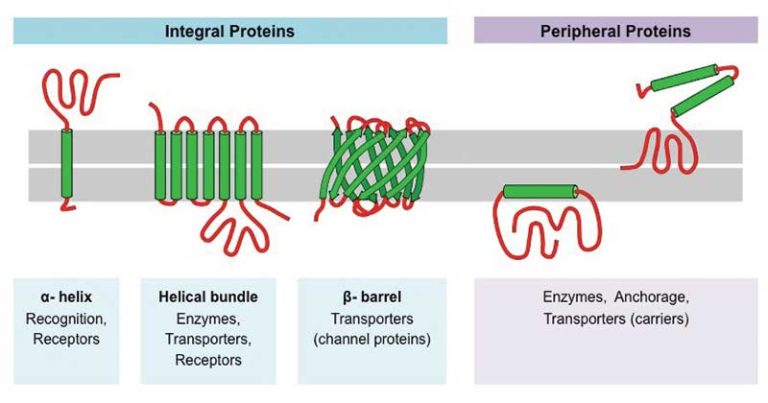

This will make it possible for researchers to design transmembrane proteins with entirely novel structures and functions,” asserted Dr. “We have shown that it is now possible to accurately design complex, multipass transmembrane proteins that can be expressed in cells. Like naturally occurring transmembrane proteins, the proteins are multipass, meaning they traverse the membrane several times, and assemble into stable multiprotein complexes, such as dimers, trimers, and tetramers. The resulting proteins proved to be highly thermally stable and able to correctly orient themselves in the membrane. Lu and his colleagues were able to manufacture the designed transmembrane proteins inside bacteria and mammalian cells by using as many as 215 amino acids. “Putting together these 'buried hydrogen bond networks' was like putting together a jigsaw puzzle,” Dr. Then it must find a way to stabilize its structure by creating bonds between the hydrophilic residues within its core.Īccording to Peilong Lu, Ph.D., a senior fellow in the Baker lab and the lead author of the Science paper, the key to solving the problem was to apply a method developed by the Baker lab to design proteins so that the polar, hydrophilic residues fit in such a way that enough of them would form polar–polar interactions that could tie the protein together from within. This means to be stable the protein must place nonpolar, water-fearing residues on its surface and pack its polar, water-loving residues inside. In membranes, however, protein folding is more complicated because the lipid interior of the membrane is nonpolar, that is, it has no separation of electrical charges. Such residues are called hydrophobic or “water fearing.” As a result, the interaction between the water-loving and water-fearing residues of the protein and the surrounding watery fluids helps drive protein folding and stabilizes the protein's final structure. Nonpolar residues, on the other hand, tend to be found packed within the protein core away from the polar aqueous fluid. As a result, polar residues on proteins are called hydrophilic, or “water-loving.” In aqueous fluids, amino acid residues that have polar sidechains-components that can have a charge under certain physiological conditions or that participate in hydrogen bonding-tend to be located on the surface of the protein where they can interact with water, which has negatively and positively side charges to its molecule. The resulting models have been shown to accurately represent the structure the sequence will likely assume in nature. It is not unusual for the program to create tens of thousands of model structures for an amino acid sequence and then identify the ones with lowest energy state. The Rosetta program can predict the structure of a protein by taking into account these interactions and calculating the lowest overall energy state. Ultimately, the protein assumes the shape that best balances out all these factors so that the protein achieves the lowest possible energy state. “Crystal structures of the designed dimer and tetramer-a rocket-shaped structure with a wide cytoplasmic base that funnels into eight transmembrane helices-are very close to the design models.”Ī protein's shape forms from complex interactions between the amino acids that make up the protein chain and between these amino acids and the surrounding environment. “The designed proteins localize to the plasma membrane in bacteria and in mammalian cells, and magnetic tweezer unfolding experiments in the membrane indicate that they are very stable,” the article’s authors reported. Actually, complex transmembrane proteins weave in and out of the cellular membrane, passing into and out of the membrane’s oily interior. Unlike proteins that operate in the watery solution that make up the cells' cytoplasm or in the extracellular fluid, transmembrane proteins embed themselves within the cell membrane. These encouraging examples notwithstanding, transmembrane protein form/function relationships are still hard to grasp. A zinc-transporting tetramer called Rocker has been engineered, as well as an ion-conducting oligomer, which emulates a bacterial design. Bespoke transmembrane proteins might be even better, dressing up cells so that they take on entirely new functions.įew transmembrane proteins, however, have come from protein designers. Transmembrane protein knockoffs might offer more flexibility. Yes, they have been tailored to serve diverse functions, from transmembrane transport to cell signaling, but they are hard to alter. Transmembrane proteins from the House of Nature are abundant, but they’re all off the rack.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)